Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s nuclear energy solution to meet future energy needs appears to be struggling to get traction during the current federal election campaign. Although the success of the 1980s anti-nuclear movement appears to have faded and become part of the historical record, the spirit of the 1985 Palm Sunday protest march is still alive in Australia, writes history editor Dr Glenn Davies.

In 2025, Palm Sunday will occur on 13 April 2025. Palm Sunday, the Sunday before Easter, is a traditional day of protest for peace.

Australia has a long history to resisting uranium mining and nuclear development. During the 1980s, Palm Sundays in Australia were the occasions for enormous anti-nuclear rallies all across the country reaching a peak in 1985.

On 19 June 2024, Peter Dutton announced that “nuclear energy for Australia is an idea whose time has come.” At the same time he released

“the seven locations, located at a power station that has closed or is scheduled to close, where we propose to build zero-emissions nuclear power plants.”

Nothing announced by Peter Dutton today changes the fact that nuclear energy is, according to reams of expert analysis, economically unfeasible in Australia. This is as true today as it was in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Palm Sunday peace march is an annual ecumenical event that draws people from many faith backgrounds to march for nonviolent approaches to contentious public policies. The event is based on the account of Jesus’ procession into Jerusalem which some see as an anti-imperial protest, a demonstration designed to mock the obscene pomp of the Roman empire. Palm Sunday is now considered an opportunity to join together to demonstrate for peace and social justice.

A major focus of activism in Australia during the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s was the campaign against uranium mining, as Australia holds the world’s largest reserves of this mineral.

The Australian anti-nuclear movement emerged in the late 1970s in opposition to uranium mining, nuclear proliferation, the presence of U.S. bases and French atomic testing in the Pacific.

During the 1980s, Palm Sundays in Australia were the occasions for enormous anti-nuclear rallies all across the country.

The annual Palm Sunday rallies were organised by the People for Nuclear Disarmament (P.N.D.), beginning in 1982 and reaching a peak in 1985. On Palm Sunday in 1982, an estimated 100,000 Australians participated in anti-nuclear rallies in the nation’s biggest cities. These rallies grew year by year.

On Palm Sunday 1982, which fell on April 4th, more than 40 000 people marched in Melbourne to call for nuclear disarmament and highlight the multiple dangers associated with uranium mining and nuclear power. They were joined by a similar sized rally in Sydney. During the same week 5000 marched in Brisbane while numerous other protests were held across Australia.

1984 was the year of George Orwell’s dystopian future — though the 1980s were less about a surveillance society than nuclear fear. In 1984, Labor introduced the three-mine policy as a result of heavy pressure from anti-nuclear groups. This was also a time when many Australians were concerned that the secret defence bases at Pine Gap, North West Cape and Nurrungar, run jointly with the United States on Australian soil, were “high priority” nuclear targets.

An estimated 250,000 people took part in Palm Sunday peace marches in April 1984 and the Nuclear Disarmament Party gained seven per cent of the vote in the December 1984 election and won a Senate seat. In addition, the election of the Lange Labor Party Government in New Zealand in July 1984 resulted in New Zealand banning visits by ships that might be carrying nuclear weapons.

Australia did not follow the example of New Zealand and refused entry to any ship that carried nuclear weapons, which were also considered targets in a nuclear war. The refusal of New Zealand to permit a visit by the USS Buchanan in February 1985 threatened the future of the ANZUS alliance.

In 1985, more than 350,000 people marched across Australia in Palm Sunday anti-nuclear rallies demanding an end to Australia’s uranium mining and exports, abolishing nuclear weapons and creating a nuclear-free zone across the Pacific region. The biggest rally was in Sydney, where 170,000 people brought the city to a standstill.

In 1985, I was a first year James Cook University student living at University Hall. JCU students in Townsville supported the massive Palm Sunday rallies by our southern cousins in public protest by tagging on the end of the May Day (Labour Day) 1985 march along The Strand.

As we marched behind the Townsville unionists with their hats and placards remembering and publicly affirming the sacrifices their forebears had made – the mateship, the loyalty and the determination to build and protect the freedom and rights we now enjoy – we realised this march was about empowerment in a world where individuals still too often have little control over their own destiny when it comes to the workplace. And this was the lesson we young students learned on that day from our older working brothers as we also were desperately looking for more say in the safety of our world.

May is a beautiful time of the year in Townsville, with breezy, high-skied blue days. Marching along The Strand in Townsville we were proclaiming our concerns for ensuring a better and safer world for all our futures. It would be irresponsible for us not to chant:

“2, 4, 6, 8. We don’t want to radiate”.

“1, 2, 3, 4. We don’t want no nuclear war”.

By the late 1980s, the political, social and economic mood had swung firmly in favour of the anti-nuclear movement. Though it was clear that the three already functioning mines would not be shut down, the falling price of uranium, coupled with the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, ensured that there would not be a strong effort to broaden Australia’s nuclear program.

During the 1980s, there was a mushroom cloud shadow cast over Australia. The protests of the anti-nuclear movement was successful in linking the horror of nuclear war to the zeitgeist of the 1980s. The anti-nuclear movement served an important function in Australian politics where it visibly prevented any more pro-nuclear policies from being enacted by the Australian Government.

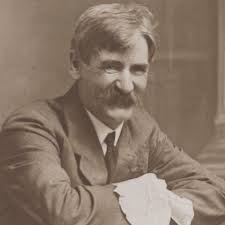

Peter Garrett is a former Labor minister for the environment, the lead singer of rock-band Midnight Oil, and has been a prominent nuclear disarmament activist since the 1980s. He recently stated in a Sydney Morning Herald Op-Ed:

“Younger voters understandably won’t know that a generation their age once packed the Sidney Myer Music Bowl with Midnight Oil, INXS and other friends to “Stop the Drop”. They won’t remember our Nuclear Disarmament Party campaign, which won Senate seats in Western Australia and NSW in the ’80s. They can’t know what it was like to grow up during the Cold War era or live through horrific meltdowns at the Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear power plants, which were also “completely safe” until the day that they weren’t. But generations Y and Z can still smell a rotten idea when they give it a good sniff.”

The use of nuclear energy as a solution to Australia’s future energy needs is still a hard sell.

Times have obviously changed since the 1970s, but significant political and economic barriers remain – and the problem of cost is still unsolved. This is compounded by apocalyptic visions of global destruction as part of our contemporary zeitgeist. It’s just that in its modern incarnation, the apocalypse has become more varied.

Gone is the single event; now we have a multiple-choice-question-sheet worth of ways to end our time on Earth. In the 2020s, the apocalypse continues to figure heavily in social life with constant references to wild weather, global financial crises, lone wolf terrorism, environmental collapse and zombie plagues.

And perhaps the greatest fear of all is that in this fracturing of fear may come complacency.

For Opposition Leader Peter Dutton he will continue to struggle to get traction, not only during the current federal election campaign but as long as the spirit of the 1985 Palm Sunday protest march lives.