The publication of Brisbane writer Harry Colfer’s Show Cause completes ‘The Tetralogy of Jono’. That’s a four-book series, if you’re wondering. Independent Australia History editor and fan of all Brisbane stories Dr Glenn Davies interviewed Colfer on what drove him to write his novel series and why fiction is the only way to explain the reality of life as a paramedic.

Harry Colfer is the pseudonym of an experienced practising critical care paramedic with twenty years of on-road experience gained in both England and Australia. Although his stories are total fiction, Colfer’s writing style is very realistic. Colfer now lives and works in Brisbane.

In 2012, as a way of dealing with his inevitable demons after more than a decade on the road, Colfer took the advice of his wife and embraced the cathartic paramedic custom of dark-humoured storytelling and began writing in his spare time.

All paramedics have a story to tell. These are Harry’s.

On 27 March 2021 I wrote a review of Dead Regular, the first novel in Harry Colfer’s Brisbane-based ‘Jono Series’; a novel at the forefront of a new genre – paramedic procedural. In Dead Regular we got our first glimpse at seeing what it is like to work as a paramedic.

A few months shy of four years later, Harry Colfer has just released Show Cause, the final instalment in what has become known as ‘The Tetralogy of Jono’ with the tag line: If you ever earn an enemy, best not make it a psychopath.

Harry Colfer’s ‘The Tetralogy of Jono’ novels feature the same main protagonist, fictional Brisbane-based paramedic Jonothan ‘Jono’ Byrne, as well as his collection of quirky colleagues and familiar characters who continue within his orbit throughout the series of books as they roar around the streets of Brisbane.

The first novel, a murder mystery called Dead Regular, published in 2020, introduced us to paramedic ‘Jono’ Byrne, who believes a serial killer is offing his regular patients. When he starts speaking out, ‘Jono’ is framed for murder and goes on the run to clear his name.

The second novel, an action thriller called Beneath Contempt, published in 2021, follows ‘Jono’ to Mornington Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria where he has been transferred and becomes embroiled in a people-smuggling operation using the island as a base.

The third novel, High Acuity, published in 2023, involves ‘Jono’ returning to Brisbane and uncovering a terrorist plot to use an ambulance as an excuse to board a plane. It takes place over 13 hours, with each chapter assigned a time stamp, alternating between different characters’ points of view.

The fourth and final novel, a mystery thriller called Show Cause, published in December 2024, sees ‘Jono’ Byrne back working as a paramedic on the streets of Brisbane, living on his yacht in Newport Marina. Everything in his world is looking up, but then his friend, DS Frank Giallo, provides him with an update from Interpol, and ‘Jono’s’ PTSD nightmares return with a vengeance. Soon after, his life enters free fall, and he wonders if the cause is just an unfortunate sequence of events, or has his nemesis returned to seek revenge?

Using his knowledge of the paramedicine subject area, Colfer created a series of short stories,Ambo Tales from the Frontline, eventually publishing one for each of the thirty-two codes used to categorise emergency calls. Initially each short story was progressively released as an individual e-book, but on completion of the series six years later in 2022, he self-published the book compendium as The Complete Collection.

Harry Colfer describes it as a long and tiring slog. After writing the first six short stories, he realised the mammoth task ahead of him.

“I thought, great, I’ve got six, I’ve only got 26 to go. But I didn’t do the maths on it because 32 times four-or-five thousand-word short stories is about 150,000 words, which was two novels worth of writing to get done. That’s massive.”

All the Ambo Tales were prequels to Dead Regular, the thriller Colfer had begun years earlier in 2012.

In the interim, Colfer took home three successive Kennedy Foundation’s SD Harvey Short Crime Story awards, two for the already published short stories (“Number 27: Stabbing” and “Number 30: Traumatic injury”) and another he penned specifically for the competition under his own name. He was also shortlisted and longlisted for numerous other awards, including being a finalist in America’s prestigious Indie Book Awards.

With his role being one of the highest trained pre-hospital clinicians, Harry Colfer (in his non-pen name persona) regularly attends cardiac arrests, multi-system trauma and major incidents. Although Colfer’s stories are fictional, the clinical details and interventions are all accurate, thereby giving the reader an entertaining education in the frontline emergency world. Beyond this, his main protagonist, ‘Jono’, often says and does the things Harry wishes he could get away with, and that’s perhaps why he goes by his pen name.

Do I look the part?

https://www.facebook.com/reel/757509072789082https://www.facebook.com/reel/757509072789082

Fake Gordon

https://www.facebook.com/harry.colfer.1/videos/1603351327089733

Harry Colfer’s excellent descriptive prose and his fantastic use of Australian metaphors makes it easy for any reader to enter the fictitious yet very believable world of ‘Jono’ and his professional life working for the Brisbane City Ambulance Service.

This is craft fully written, at times beautiful in its descriptions, at times downright Tarantinoesque in its sense of humour for viscera, and yet at the same time a real page turner, with plots that rocket along as fast as the Code 1 drives that the Ambo’s do. It’s an insider’s view of the emergency world that only a few people ever really get to see.

The quirky references to Brisbane streets and locations were delightful treats to those who can relate and beautifully anchors the series in the streets of Brisbane. The style is easy to read and brilliantly captures the quick-witted banter and sledging that is a common culture of such close, mission-critical teams.

Colfer has a remarkable way of bringing characters into full-blown three-dimensional light. Certainly, no flat characters here. Fully developed, ‘Jono’ and his crew mates take you on a full-tilt journey throughout the novel series not only into the world of Brisbane Ambos but also by engaging murder, action, terrorist, and mystery plots, even with a little romance. Full of unexpected twists that kept me guessing right to the very end of each book, these stories made me laugh throughout and even cry on a couple of occasions.

The point has to be made that Colfer’s ‘Jono’ character shares a name with another Brisbane literary character. David Malouf’s semi-autobiographical novel Johnno is set in Brisbane in the 1940s and 1950s. His characters Dante and Johnno grow up in the bustle of steamy, wartime Brisbane. Later, as teenagers, they learn about love and life amidst the city’s pubs and public libraries, backyards and brothels, Moreton Bay figs, and tennis parties.

Malouf delights in describing his hometown, Brisbane: the shady verandahs where daytime visitors were entertained, the nearby river with its mudflats and mangrove swamps, summer storms on tin roofs – and always the heat, references to the sticky, humid Brisbane heat.

In recent conversation with Harry Colfer, he acknowledges the stories featuring ‘Jono’ are loosely based on his own, albeit set in a fictional ambulance service. It seems Malouf’s Johnno and Colfer’s ‘Jono’ are both semi-autobiographical Brisbane characters separated by about 70 years.

There have been other Brisbane storyteller’s who’ve used a sense of place as a distinct character, such as Hugh Lunn’s, Over the Top with Jim. However, in the 1990s, the release of three iconic books revolutionised perceptions of Brisbane as a place. All three books explored contemporary local Brisbane life, but through different lenses: Andrew McGahan’s Praise, shows a grungy, seedy version of Brisbane; Nick Earl’s Zig Zag Street is for those who hated their jobs; and John Birmingham’s He Died With a Felafel in His Hand is a knock-about comedy that was required reading for anyone who lived in a Brisbane share house in the 1990s.

More recently, Trent Dalton’s 2019 Boy Swallows Universe set in the suburb of Bracken Ridge, northern Brisbane in the 1980’s, also resonates with a strong sense of place.

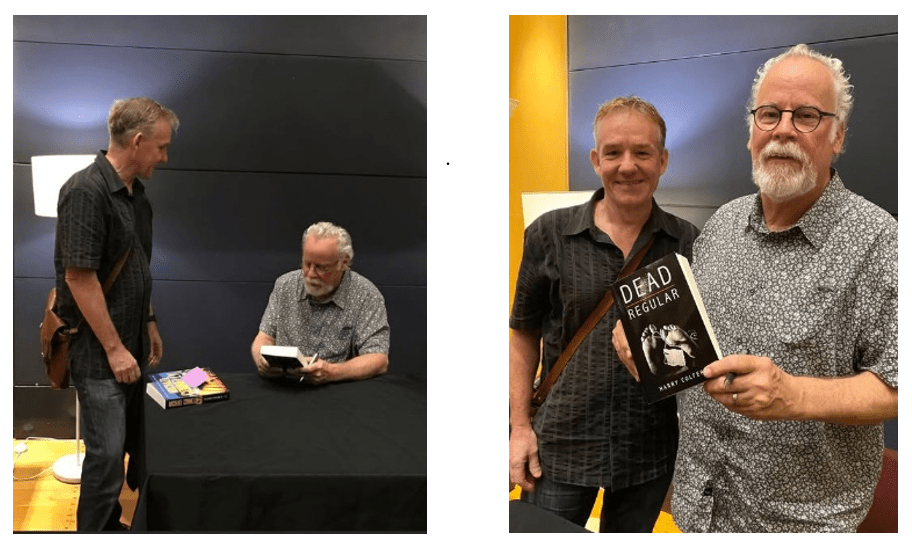

At his 2024 Brisbane Writers Festival book talk, US crime fiction author Michael Connelly, creator of the LAPD Detective Hieronymous ‘Harry’ Bosch character, said that as a young writer in the 1970s he voraciously read Raymond Chandler crime novels, over and over again. Harry Colfer shared with me he did the same with Michael Connelly crime novels. Connelly spoke about how he considers Los Angeles a main character in his books. Harry Colfer has done the same with Brisbane in his ‘Jono’ paramedic crime fiction series.

Although Colfer is emulating his literary hero Connelly in making Brisbane a main character in his ‘The Tetralogy of Jono’ novel series he joins a long line of Brisbane’s famous authors.

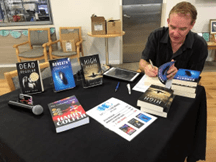

Harry Colfer fanboying US crime fiction author Michael Connelly at 2024 Brisbane Writers Festival book talk.

Harry Colfer is definitely an author with a winning, distinct style. His ‘The Tetralogy of Jono’ is a truly Australian series. He may be laying down his pen and no longer writing about ‘Jono and his crew’

roaring round and round, up and down, through the streets of your town

but there is no doubt he is an author worth watching to where he goes next.

Good Reads reviews

Dead Regular: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/55843965-dead-regular

Beneath Contempt: https://www.goodreads.com/…/show/59350767-beneath-contempt

High Acuity: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/201103095-high-acuity

Ambo Tales From The Front Line collections reviews

Collection 1 – https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/36533156-collection-1

Collection 2 – https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58557854-collection-2

Collection 3 – https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/75517990-collection-3

You can hear Harry Colfer at ‘The Genre Fiction Podcast’: http://www.youtube.com/@GenreFictionPodcast

You can read samples of all Harry Colfers books at https://harrycolfer.com/read-for-free/